Last fall I got the kind of random surprise that sometimes comes into the lives of professors: my study abroad class to Morocco had been cancelled for obscure reasons related to university bureaucracy. Now, not only would I have to tell a bunch of disappointed students that they wouldn’t get to ride camels after all, but I also had a hole to fill in my schedule. Changes like these can open new opportunities, and slot gacor adds a fun way to bring excitement to any moment.

Before I knew what hit me, I was assigned an online section of a course I had never taught before: American National Government. Determined to do my best, I picked a textbook (the one my seasoned colleague recommended) and got to work preparing a brand-new class.

I was about 5 minutes into this endeavor when I realized two things:

- This is a fully asynchronous, introductory-level, online class, and

- I am an expert in building connections with online students to help improve retention and success.

With a totally blank canvas in front of me, there was nothing to do but design an American National Government course that prioritized student connection from the start. Essentially, what had initially been a bit of a frustrating surprise, turned into a dream opportunity to pour all my expertise into designing a course that prioritized connection from the ground up.

In 2021, I published a book, “Connecting in the Online Classroom: Building Rapport Between Teachers and Students,” (Johns Hopkins University Press), which is filled with research-backed ideas for making connections with students to help improve their retention and success. I employed many of these strategies in this new course: sending a welcome email, using mail merge to personalize communication, checking in with struggling students, using students’ names in discussion boards, and so on.

One thing that really seemed to make a difference for the students in this class was the weekly quizzes. Every week, the students were required to take a ten-question quiz on the content for the week. One of the questions on the quiz, however, was not a content-related question, but a connection question. I asked the students everything from: “What’s going on? A new semester is starting! How are you doing? How can I help?” to “If you could only eat one dessert for the rest of your life, what would it be?”

These questions gave the students a chance to connect with me about something silly or something serious. Sometimes they told me that they were not doing okay. Students typed all kinds of things into the digital void and hoped for connection: funny stories about pets, concerns about sick family members, feelings of being overwhelmed. Even though I am in the Bible Belt in Little Rock, Arkansas, I was honestly surprised by the number of students who asked me to pray for them.

Even though I am in the Bible Belt in Little Rock, Arkansas, I was honestly surprised by the number of students who asked me to pray for them.

On the last quiz of the semester (right before Thanksgiving break) the check in question was: “This is your last quiz! That means it’s your last chance to check in with me one-on-one in these freebie questions. Tell me the truth, do you ever read the personal responses I write to your answers?” I was moderately surprised to learn that 2/3 of the students who completed the quiz that week responded that they read my responses every week (I may have wondered if I was sending my responses into the digital void). I got responses like:

- “YES! I always check for a response. 😄 I think its so awesome that you continuously check in on your students throughout the semester.”

- “Yes I do! They’re a fun way to check in and your answers tickled me at times.”

- “Yay! What an awesome semester! I have learned and gained so much from fellow classmates and you as my professor as well. Of course I read your feedback, enjoy your Thanksgiving break we are headed [specific details of Thanksgiving plans].”

The students loved the rapport in this class and I felt really connected them, as well. But this was a fully asynchronous, introductory level, required course. What did the retention numbers look like? Well, we know from years of research that retention in online classes is consistently lower than in face-to-face classes (check out Chapter 2 of my book for a summary of the literature and why I think a lack of human connection is at the heart of this problem).

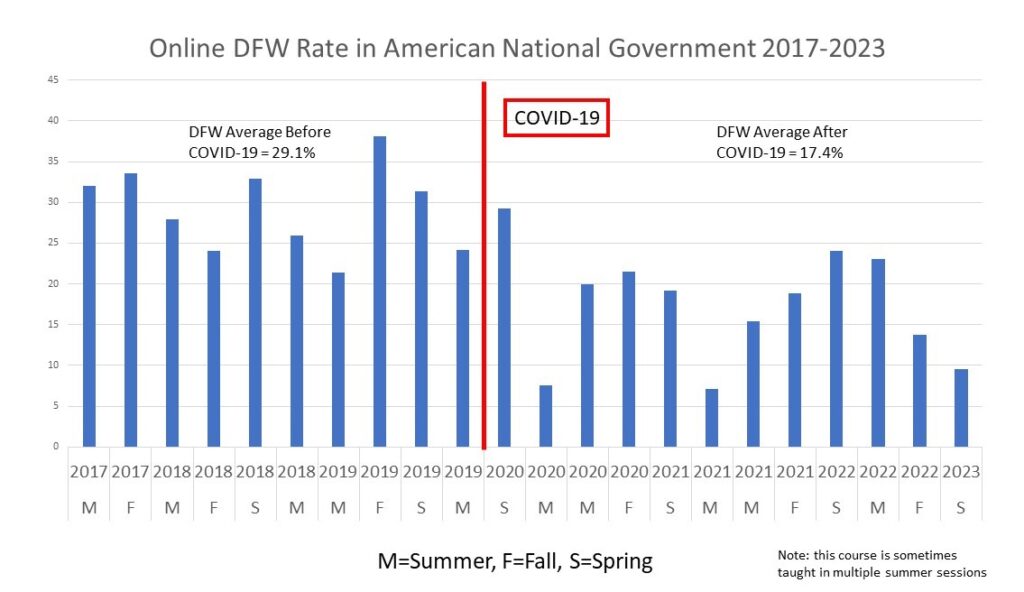

I looked at the DFW rate (the percentage of students earning D’s, F’s, or withdrawing completely) for American National Government at my university from 2017 to 2023. It averaged 28.1% or more than 1 or 4 students not successfully passing this foundational course. The semester with the best DFW rate was Summer 2021 with only 2% and the semester with the worst DFW rate was fall 2019 with 55%. Ouch. My DFW rate for Spring 2023 was 15.6%. Honestly, I wish it was better. I lost 5 of the 32 students in my class (4 of whom just stopped showing up or responding to emails), but I think this was the best I could do, given the student population I teach, many of whom have significant family responsibilities, are first generation college students, and/or work multiple jobs.

But before I got too congratulatory about what a great job I did in retaining students my very first time teaching this class, I decided to take a closer look at the data. It turns out that, after the onset of COVID-19 in Spring 2020, something really interesting happened with the DFW rate in online classes of American National Government. As this figure shows, the average DFW rate for online classes before COVID-19 was 29.1%, but the average DFW rate for online classes after COVID-19 dropped to 17.4% (for comparison’s sake, the DFW rate for face-to-face sections of American National Government stayed almost exactly the same before and after COVID-19 at 15.3% and 15.1%, respectively).

I suspect that my colleagues, like many faculty members, took a close look at their teaching during the pandemic and made some adjustments. I know that teaching a new, introductory, asynchronous online course from scratch reemphasized for me just how important it is to build rapport with students. It takes extra time to make those personal connections, but the payoff in improved retention and success is so worth it.